Python regius Natural History

b a l l p y t h o n / r o y a l p y t h o n

Physical Description

Wild-type P. regius, also called ball pythons or royal pythons, are generally black to dark brown with large lighter markings described as “key-holes” or “alien-heads” depending on the number of dark spots within each marking. These patterns shape the darker base-color into rounded bands called the “puzzle” pattern. Their heads have yellow stripes beginning at the nostrils that pass through the eyes. The belly is typically white with black flecks laterally.

Hatchling ball pythons range from 25 to 43 centimeters (10-17 inches) in length and grow to 1 to 1.5 meters (3-5 feet) as adults. Their peanut-shaped heads are larger than their relatively slender necks that lead to an otherwise round, heavy body [3]. Their upper lips have multiple indentations called heat pits to detect infrared radiation from their warm-blooded prey.

Figure 1. An adult ball python in the wild.

Figure 2. A hatchling leopard ball python bred in captivity.

Figure 1. Photo by Aaron Gekoski.

Figure 2. Photo by Samantha Hall

Geographic range

P. regius is native to western Africa and northern parts of central and eastern Africa from Senegal to South Sudan and Uganda. [4] More specifically, this includes the “Sudanese subprovince west of the Nile, in southern Sudan, the Bahrel Ghazal and Nuba Mountains Region, from Senegal to Sierra Leone in West Africa, and in the Ivory Coast and some parts of Central Africa” [3].

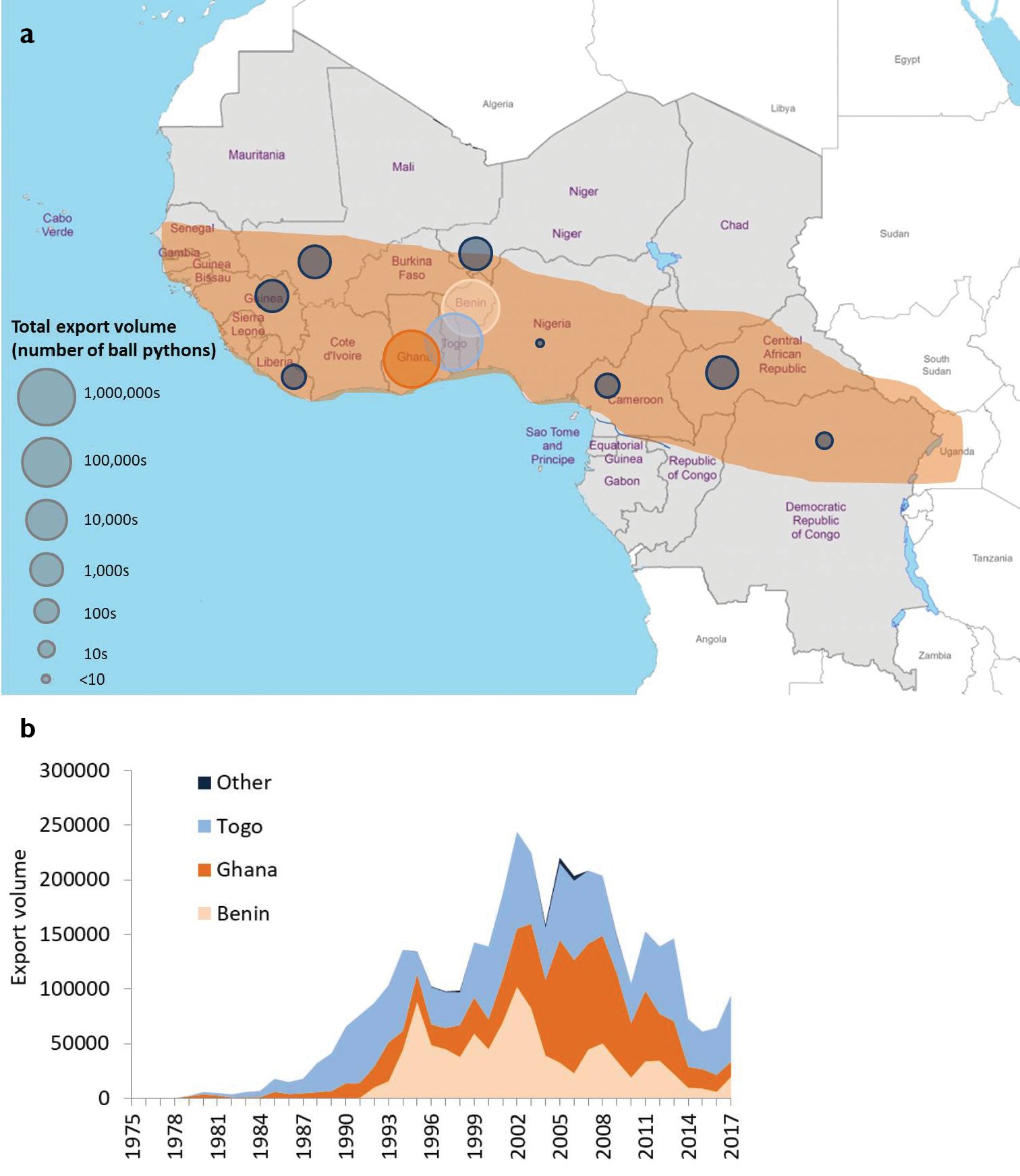

Over three million individual ball pythons have been exported from West Africa since the first recorded exports in 1982, predominantly for consumers in the United States of America, Europe and Asia. More than 98% of ball python exports from Range States originate from Togo, Benin and Ghana. [1]

WHY THIS MATTERS: Knowing the natural range of a species and the habitats found there can help keepers better understand their needs in captivity.

Based on the featured distribution map, Figure 2, most ball pythons exported from Africa since 1976 have been taken from Ghana, Togo, and Benin. Examining the habitats in these countries can help inform proper care for P. regius.

Figure 3a shows the approximate distributional range of ball pythons in west and central Africa shaded in orange. The colored circles show the relative export number of ball pythons exported from individual countries from 1978–2017.

Figure 3b shows trends in annual exports for the three main exporting countries and all others combined.

Figure 3a and 3b by Harrington LA, et al. [4]

Habitat

P. regius is found in a wide range of savannah habitats, including open woodlands, the edges of rainforests, and agricultural land. They are nocturnal [4] and are found to be most active at dawn and dusk [3]. P. regius spends most daylight hours hiding in abandoned tortoise or rodent burrows, termite mounds, or under dead oil palm trees and piles of grass and leaves [4]. Multiple pythons may inhabit the same burrow, except brooding females, which are more likely to be found alone (Murphy et al., 2003).

WHY THIS MATTERS: Based on observed behaviors in the wild, P. regius should be given the opportunity to spend most of the day hidden and allowed to explore at night. Their preferred habitat is also generally cluttered, allowing the snake to be obscured even while exploring.

Figure 4. A termite mound in a savannah of Northern Ghana. P. regius can commonly be found hiding in abandoned burrows dug into these impressive structures.

Figure 5. A savannah in Northern Ghana.

Figure 4. Photo by Fuseini Dipantiche Mohammed Naporoo Kamal-Deen Shitobu on Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Diet in the Wild

P. regius eats rodent prey native to their range, including grass mice, shaggy rats, rufous nosed rats, and African giant rats [3]. These snakes have also been found to eat large quantities of nestling birds, especially young snakes and males [5].

WHY THIS MATTERS: Ball pythons eat primarily small mammals and birds; therefore, the prey items typically available to captive snakes (African soft furs, rats and mice) are only close approximations to their natural diet.

Author’s note - The topic of “arboreal ball pythons” is contentious in the hobby; however, studies have shown that a large quantity of males specifically were found in the trees during the day. Whether this is out of necessity, including searching for prey or escaping flooded ground dwellings, or regional differences in behavior, I cannot say.

Figure 6. An African giant rat, Cricetomys gambianus, trained to detect land mines.

Figure 7. A grass mouse, Lemniscomys striatus, in Kakamega Forest, Kenya.

Figure 6

Figure 7. Photo by Charles J. Sharp

Hunting Style

The majority of P. regius, especially females, are sit-and-wait ambush predators. [3] In one study, males were frequently found in trees during the day and were found to eat small birds. [5] Regardless of hunting strategy, the snake will strike and immobilize its prey through constriction before swallow the prey whole.

The ambush strategy means these snakes are designed to rarely eat. Infrequent feeders have adapted by having the capacity to widely regulate gastrointestinal functioning with feeding and fasting.

WHY THIS MATTERS: Ball pythons spend a lot of time hiding and waiting for prey; therefore, they need secure places to hide to be healthy in captivity.

In addition, these snakes, especially females, should be fed larger meals infrequently to emulate their hunting patterns in the wild. However, opportunities to roam and climb should also be provided, especially for males.

Figure 8. A ball python uncovered from a rodent burrow

Figure 9. A captive juvenile ball python constricting their prey and preparing to swallow it whole.

Figure 8. Photo by D’Cruze N et al [1]

Figure 9. Photo by Alexander Shenkar on Flickr

Sexing and Sexual Dimorphism

WARNING: Do not attempt the following procedures without training from an experienced keeper.

The sex of a ball python can be determined through probing or popping.

In probing, a small metal probe is gently inserted into the cloaca caudally to travel into a cavity made by the inverted hemipenes in a male snake. The probe will travel deeper into the base of the tail for male ball pythons, spanning 8 to 10 subcaudal scales, in contrast to females, which should span 2 to 4 subcaudal scales. [3]

The hemipenes can also be extruded, or “popped” by placing external pressure on the region just below the cloaca with a finger; however, this procedure is potentially dangerous and should only be performed by trained professionals.

Adult female ball pythons are generally larger than adult males, but this difference can not be seen in hatchlings. Female ball pythons reach reproductive maturity from 27 to 31 months at approximately 1500g. Males reach reproductive maturity at 16 to 18 months at approximately 400g. Both males and females have cloacal spurs so they cannot be used to sex an animal. [3]

Figure 10. This diagram shows the differences seen when probing P. regius. A female is on the left and a male is on the right. Note that both sexes have cloacal spurs.

Figure 10. Diagram by Vetfolio.

Reproduction

Ball pythons have long reproductive lives that last from maturity at 16-31 months to the end of their lives, up to 30 years. In their native range, the breeding season is primarily from mid-September through mid-November, correlating with the minor rainy season. Most females lay their eggs during the second half of the dry season, from February to April after 44-54 days of gestation. Eggs are then hatched from April to June. [3]

If successful copulation has taken place, or a “lock”, follicles will develop until the female ovulates. Approximately 3 weeks after ovulation they will have a pre-lay shed. After this, eggs can be expected to be laid about in about 4 weeks. (De Vosjoli, et al., 1995)

A clutch is typically from 1 to 11 eggs with 7 being the average number. [2] The eggs typically adhere to each other upon laying to prevent the eggs from shifting and potentially killing the fetus. After laying their clutch of eggs, the female will coil around their clutch until hatched after approximately 2 months. [3]

Ball pythons have a strong maternal instinct that persists until the eggs hatch. According to a clutch-size manipulation study, “brooding female pythons may enhance the survival of their offspring in three ways: by repelling potential egg predators, by maintaining high and constant incubation temperatures, and by retarding desiccation of the eggs.” [2] Females have even been shown to shiver to warm their eggs as well as run their bodies through water to increase the humidity of the eggs and prevent water loss.

When fully developed, the neonates will cut a slit in the shell of their egg with their egg tooth and exit the egg. Hatchlings typically weigh between 65 and 103g. [3]

Figure 10. Photo by Samantha Hall.

Figure 11. Photo by the St. Louis Zoo

Comments? Questions?

Contact us.

The Author

Samantha Hall is the founder of The Vivarium and has been breeding exotics since 2010. She is currently a veterinary student at Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine and has a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Michigan. She participated in three years of wildlife field research and was exploring nature since before she could even walk. Also pictured is her first ball python, Hissahr, a classic adult female.

Works Cited

[1] D’Cruze N, Harrington LA, Assou D, Ronfot D, Macdonald DW, Segniagbeto GH, Auliya M. Searching for snakes: ball python hunting in southern Togo, West Africa. Nature Conservation 38: 13-36. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.38.47864

[2] Fabien Aubret, Xavier Bonnet, Richard Shine, Stephanie Maumelat, Clutch size manipulation, hatching success and offspring phenotype in the ball python (Python regius). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 78, Issue 2, February 2003, Pages 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00169.x

[3] Graf, A. 2011. "Python regius" (On-line). Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Python_regius/

[4] Harrington LA, Green J, Muinde P, Macdonald DW, Auliya M, D'Cruze N (2020) Snakes and ladders: A review of ball python production in West Africa for the global pet market. Nature Conservation 41: 1-24. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.41.51270

[5] Luiselli, L., & Angelici, F. M. (1998). Sexual size dimorphism and natural history traits are correlated with intersexual dietary divergence in royal pythons (python regius)from the rainforests of southeastern Nigeria. Italian Journal of Zoology, 65(2), 183–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/11250009809386744